Order From Chaos

Grasping onto the Jewish framework through tumultuous times has maintained us for thousands of years. It still works.

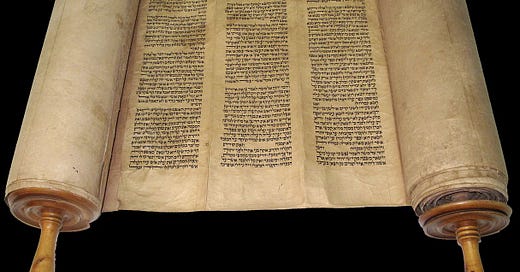

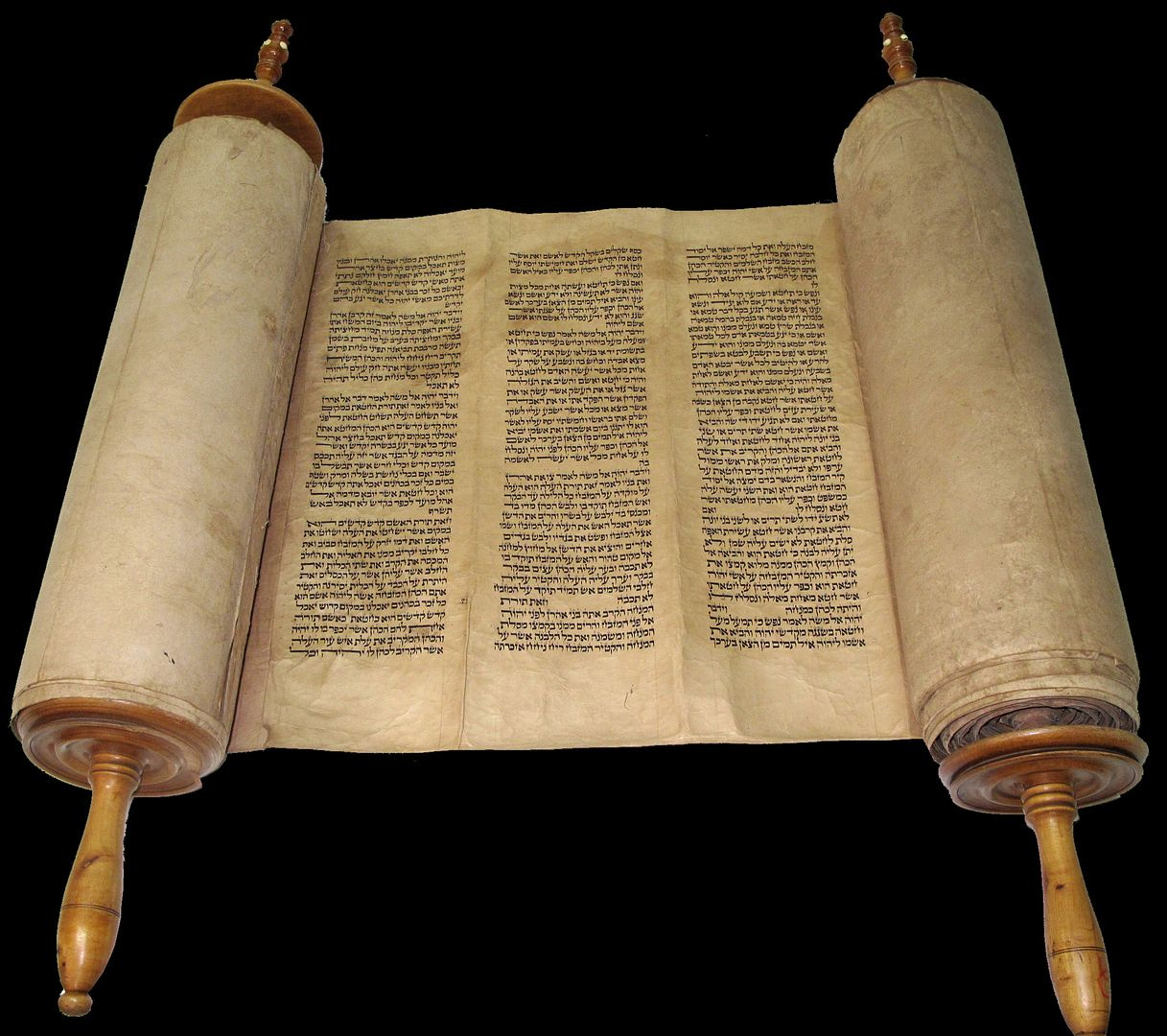

The Torah is not an orderly book. Anybody who has looked closely at the jumble of stories, laws, verse fragments, occasionally conflicting instructions and so forth found therein quickly sees that it is a pastiche of materials drawn from different sources.

Sure, when you are looking at the Hebrew text from a distance - neat columns in handsome script on parchment - it seems organized, and while we absolutely cannot deny its essential holiness and its supreme role in our lives as the foundational text of the Jewish bookshelf, we also must concede that it is occasionally messy. And, lest you think that later Jewish texts are more organized, let me assure you that our tradition is not at all systematic. (I always have to chuckle when people talk about their rejection of “organized religion,” and I think to myself, “You call THIS organized?!”)

And in that regard, the Torah is something like our lives: an attempt to calm the forces of chaos, a valiant effort to impose some order on our daily existence, which always features the unpredictable.

In thinking about just the last two weeks on the national stage, we are confronted with a certain amount of what you might call “unprecedentedness.” An attempted assassination of a former president and current presidential candidate, resulting in the death of an innocent bystander. A current president and presidential candidate ending his run and anointing a third presidential candidate, who is also the sitting vice president. An address of a joint session of Congress by the Prime Minister of Israel, accompanied by violent protests outside featuring the burning of American flags and outright support of terrorist organizations.

It’s been quite a wild ride. Nobody will look back on the summer of 2024 and think, “That was some smooth sailing.” And, of course, the summer is hardly over. I have some deep concerns about what might take place at the Democratic National Convention, particularly outside, but perhaps inside as well.

Parashat Pineḥas is, from start to finish, entirely about imposing order on chaos. The parashah opens (as Noa mentioned) with God upholding the zealous actions of Pineḥas, who murders an Israelite, Zimri ben Salu, and and his non-Israelite partner in flagrante delecto. Then there is a census, the second in this book of Bemidbar, which is focused on defining who gets what pieces of land when they enter Israel. And then there is the matter of God’s ruling regarding Benot Tzelofḥad, the daughters of Tzelofḥad, who, as it turns out, can inherit from their father since they have no brothers. And then we get to the most frequently-read passage of the Torah throughout the year: the list of sacrifices for the entire yearly cycle of holidays.

Each of these things, even the introductory bit about the, shall we say, complicated actions of Pineḥas, is effectively about defining a framework. One might ask, since there was a census at the beginning of Bemidbar, why did they need to do it again? One answer, suggested by the text, is that there was a plague to cleanse the community of those who had sinned like Zimri, so they needed to recount.

But maybe this census comes from a place of anxiety. Have you ever recounted, let’s say, place settings before a dinner party, just to make sure you have the right number? Or gone over the numbers on your tax return a second or third time? Of course you have, because you want it to be right. The whole point of this journey bemidbar, in the wilderness, is to prepare to inherit the land of Israel. These forty years are an attempt to bring order to chaos, to create a framework for Israel that brings together land, peoplehood, and matters of the spirit. So they are anxious about getting it right.

It is very hard for us not to feel challenged today by all of the turmoil in the world, and all the more so that in our own lives. I think it is difficult to make the case that things are worse than they have ever been. After all, we live in a world in which we were able to create a vaccine for a deadly virus in under a year. We have improved agricultural technology so that we can feed far more people than we ever could. We may not be able to prevent hurricanes, but we know when and where they will hit. Infant mortality, though certainly not eliminated, is much lower than it ever was. There are so many ways in which we can demonstrate that human existence is much less deadly and much more enjoyable than it has ever been. Some day, maybe, we will cure cancer and Alzheimer’s and find a workaround for global warming.

But for many of us, the sense that we are backsliding, that the stability of the world order is unraveling, that the hard lessons learned from the ravages of the great wars of the 20th century are being forgotten, is difficult to ignore.

Part of that may be that we simply have so much more information than we used to. Consider the following: If you follow pretty much any news source, you will be served a steady diet of upsetting news about horrible things going on in the world. If you type the name of any disease into a search engine, you will be served a series of the most horrible pictures of people suffering from that affliction. We hear on a daily basis how this thing is bad for you or that activity is destroying the Earth.

No wonder rates of anxiety and depression continue to rise, especially among young adults.

Our challenge is sorting out what are the things over which we have control from those over which we do not. I’m sure you have heard of the “Serenity Prayer,” (originally attributed to 20th c. American Protestant theologian Reinhold Niebuhr). In its most widely-known form, it goes like this:

God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

Courage to change the things I can,

and Wisdom to know the difference.

There is a rough analog from the Jewish bookshelf, sometimes mis-attributed to the 11th-century Spanish poet Shelomoh Ibn Gevirol, but actually from a 15th-century anonymous wisdom collection known as Mivḥar Peninim (17:2):

רֹאשׁ הַשְׂכֵּל הַהַכָּרָה בֵּין הַהֹוֶה וְהַנִּמְנָע. וְהַנֶּחָמָה בְּמָה שֶׁאֵין הַיְּכֹלֶת

Intellectual pre-eminence consists of discriminating between the probable and improbable, and being reconciled to the uncontrollable.

In other words, we have to be mindful of what may happen, even though we can neither predict nor control the future, so we must accept and manage what comes our way.

What we learn implicitly from Parashat Pineḥas, and, one might say, much of the Torah’s attempt to shape our lives through ritual, through law, through the values we see in our ancestors, through the mitzvot which highlight the holiness in our lives and in our relationships with others, is that despite the fact that there will always be chaos, despite the fact that we have little control over what is to come, we can manage the future by holding onto the framework that our tradition gives us.

And in practice, we learn from Jewish history that, in times of upheaval, in times of destruction and exile and dispersion and persecution and genocide, we have persisted. That is why we still mark Tish’ah BeAv by chanting the book of Eikhah, Lamentations, and kinot, poems of lament from throughout our history. We do so to recall that, although some things might seem really awful today, if we compare to, let’s say, destruction of Jerusalem and exile at the hands of the Babylonians, well, maybe it’s not so bad after all.

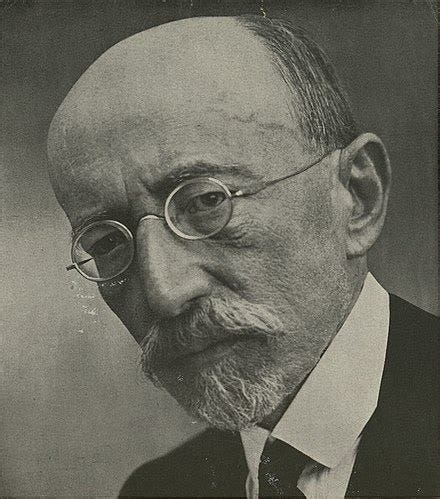

In surveying Jewish history, I see what must be obvious, even though it may be hard to prove scientifically: that we are still here, davening in (of all places) Pittsburgh in 2024, 1954 years after the Romans destroyed the Temple in Jerusalem and ended the sacrificial practices described in Parashat Pineḥas, because we managed the chaos by clinging to our traditions. It must be because we still gather for prayer in our ancient tongue, in place of those sacrifices; it must be because we still retell our origin story as we read the Torah through each year; it must be because, as Aḥad Ha’Am put it, “More than Jews have kept Shabbat, Shabbat has kept the Jews.”

We have continued to bring a semblance of order to our lives even as mighty empires rose and fell, even as we traveled across oceans and continents and eras to arrive at the present moment.

As I have grown in my rabbinate, I understand this more and more: what keeps us as Jews, and helps us manage the turmoil, is that holy framework to which we have been clinging for thousands of years. And we must continue to hold on, for the benefit of our children and their children, and all the generations who will follow, so that whatever happens, we will still be here to support one another and bring Torah to the world.

As always, Rabbi, thank you for your cogent and thoughtful perspectives on our past, present and future.

When I was learning Parshat Pinchas in preparation for my Torah book, I was repulsed by that man’s vicious energy and self-righteous actions regarding the two ‘ sinners’ that he mercilessly butchered for their sexual liaison. In addition, I was irritated by his reward of a priesthood for those actions. For me that parsha amply illustrated the vengeful aspect of God that is so well duplicated in all of us at times. Perhaps the story was put there as a cautionary tale for us, I do not know. Nevertheless, its outcome resonates in our politics and national discourse today. As you say, in echoing the wiser heads of our past, we must understand what is happening around us yet accept the fact that we are limited in how we may respond to it.

While I agree with you about the importance of preserving our traditions and philosophy, I think we must also except the importance of reinterpreting our liturgy with the perspective of our own times.