Heavy Text and Intersubjective Reality

Carrying our ancestors, and our whole tradition, in our ongoing journey. Vayḥi 5785.

I am currently reading the Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari’s new book, Nexus, which is about artificial intelligence, and it is as much a cautionary tale for the future as well as a fascinating history of shared human ideas.

One of the principles that is essential to understanding the great potential and very real dangers of AI is the concept of “intersubjective reality,” which is a mutual understanding by a group of people that certain ideas are valid. Money, for example, which we all agree is real, is actually a shared idea: we all believe that particular papers and certain plastic devices represent currency. It is so real that we have created whole systems and governments and commercial organizations which depend on this idea. Law, philosophy, and of course religion all fall into the category of intersubjective reality.

Harari spends a certain amount of time talking about the development of Judaism over the last couple thousand years as an example of how intersubjective ideas must be self-correcting in order to maintain their viability. When the Second Temple, a very real thing which was very, very important to the Jews, was destroyed by the Romans in the year 70 CE, Judaism successfully self-corrected, transitioning from a centralized, hierarchical tradition based on sacrifice of animals and produce, to the democratic, book-centered collection of stories and wisdom and rituals and halakhah / Jewish law which we know today. It was a fabulously successful paradigm shift which enabled Judaism to continue to thrive, even as the Jews were forced out of Jerusalem and Israel. This self-correction that our sages put in place created this new intersubjective realm, and enabled us to live in a refashioned Jewish reality. That is why we are here today celebrating calling a young man to the Torah as a bar mitzvah, something which was likely NOT done before the Romans destroyed the Temple.

One of the essential principles of our tradition, what enabled us to make that jump from a single worship center in Jerusalem to synagogues all over the world, wherever the Jews are located, is the idea that we carry our ancestors with us wherever we go. When we began the Amidah for Shaḥarit earlier this morning, we invoked Avraham, Yitzḥaq, Ya’aqov, Sarah, Rivqah, Raḥel, and Leah. And we will do so again in a few minutes. We connect ourselves to those ancient folks whenever we read the Torah. We continue to tell their stories, and cite midrashim about them which help guide us through our lives.

And this idea of carrying our ancestors with us is drawn from the Torah itself. In Parashat Vayḥi, as our father Ya’aqov prepares to die, he requests that he be buried not in Egypt, but alongside his father Yitzḥaq and grandparents Avraham and Sarah in the cave of Machpelah, back home in Israel (Bereshit/Genesis 49:29-32). And indeed, when Ya’aqov dies, Yosef takes him back to Israel for burial. And not only that, but Yosef is accompanied by all the senior dignitaries of Egypt, including chariots and horsemen, and of course all of Ya’aqov’s family (50:7-9).

A few hundred years later, when the Israelites flee slavery in Egypt, the Torah notes that Moshe takes the bones of Yosef with him as they depart (Shemot/Exodus 13:19). A midrash found in the Mekhilta tells us that the act is a symbolic one. In carrying Yosef’s remains, Moshe acquires Yosef’s strength of leadership, his ability to provide food and spiritual guidance as well as his capacity for forgiveness.

And, metaphorically to this day, we have carried our ancestors with us. We tell and retell their stories; we live their values; we share their wisdom. And, particularly following the Roman destruction and dispersion of the Jews from our land 2,000 years ago, we have had an extensive journey through many places and continents and cultures, all the while carrying our people with us. And we draw on their spiritual leadership as well.

And somewhat less metaphorically, we have carried all of Jewish life with us as well. The books, of course, but also the rituals and customs, the collective behaviors of Jewish life, our mitzvot. The intangibles and the tangibles: tefillah/prayer as well as the Torah scrolls and tallitot and tefillin and ḥanukkiyot and ḥallah covers and seder plates and kiddush cups and all the ritual paraphernalia which our people have used to help us fulfill and maintain our spiritual framework for two millennia.

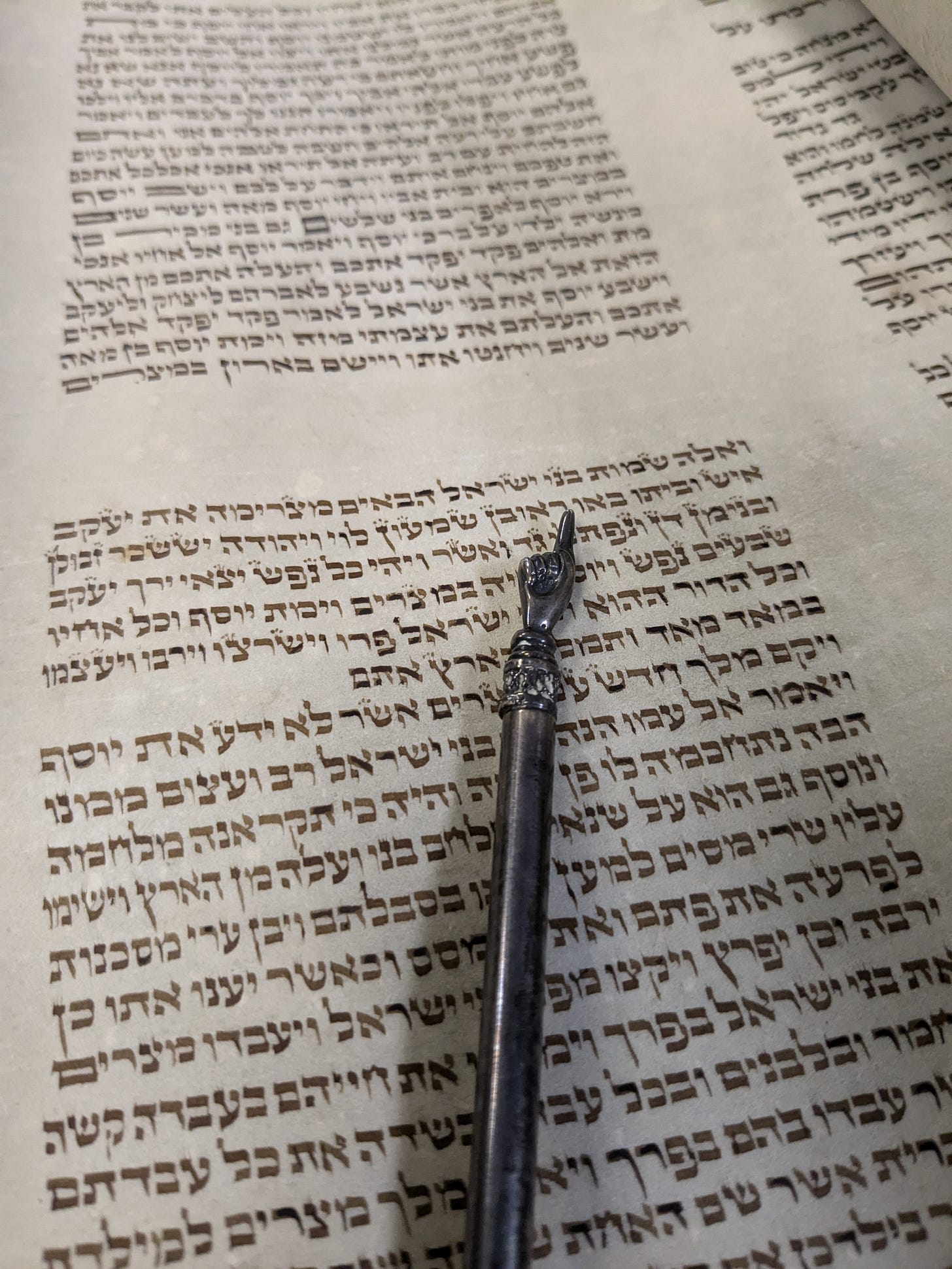

While the wisdom of the Jewish bookshelf has sustained us both in times of darkness and light, these physical objects have given us material reassurance, something to literally hold onto in times of need. I remember sitting next to my father as a little kid, playing with the tassels hanging from his seemingly ancient tallit, which he had received when he became bar mitzvah. I recall reading Torah on the day I was called to the Torah as a bar mitzvah, clutching the silver yad in my hand anxiously, holding on for dear life. When we grasp our ritual objects, when we drape them or wrap them or polish them, we are lifting up our ancestors once again; we are drawing on their spiritual leadership and making it our own.

And that is one reason why we are zealously traditional about ritual items here at Beth Shalom. That is why we have historically expected boys and men to wear a kippah, and if they are benei mitzvah, tallit and tefillin at appropriate times. Our ritual garb, which we have carried with us, consists of essential, physical items which announce and maintain our commitment to being Jewish.

And yes, use of those items was, not too long ago, only for men and boys. But think of how immensely wonderful it is that we live in a time in which women can choose to array themselves in these items as well! To opt in to carrying our ancestors in a tangible way. As R. Yehoshua ben Levi tells us multiple times in the Talmud, women too are part of the mitzvah. And we at Beth Shalom are proud that we have many women who take on these rituals.

It is worth knowing that there has been some recent discussion at our Religious Services Committee about our expectations for the use of these ritual items. Let me assure you that as guardians of the bones of Yosef, and consequently his spiritual leadership, that we will not let go of this expectation for men. But we are still considering how we can encourage more women to do so. Not require, most likely, because there are many women for whom this will not be comfortable. Our goal is to raise the bar in terms of fulfillment of mitzvot, and hope that more will reach higher. And so in the coming months I hope that you will hear and see more on this subject as we clarify our language and goals.

In the wake of the heartbreaking destruction in Los Angeles, I heard an interview with the Cantor Ruth Berman-Harris (here beginning at 2:00 min) of the Pasadena Jewish Temple and Center, a Conservative synagogue whose building was totally destroyed by fire. She, along with her husband and a few congregants, went into the smoke-filled building, after the power had gone out, to rescue the Torah scrolls. And she said something which struck me, that the Torah scrolls are the “heartbeat of Jewish life.” She did not say, the text of the Torah, or the wisdom contained therein, or all the commentary that has flowed from Torah over the last few thousand years, but the scrolls. She pointed out that through all that Jews have faced - pogroms, antisemitism, and even natural disasters - we have always strived to save the scrolls themselves, even though we know that the words are indestructible.

The interviewer asked, “Are they heavy?” And of course she responded yes. But what she did not say was that they are heavy with tradition; they are heavy with the presence of our ancestors. They are heavy with history and culture and language and philosophy and all that we carry with us.

And the journey, the same journey of Yosef and Moshe Rabbeinu and the 40 years in the desert and every place where we have been since, has been a long, hard journey, and we are still carrying it all. And we have not yet arrived. We are still traveling what Yuval Harari might call an intersubjective journey, but the results are very real. And that is why, even as we self-correct, we cannot loosen our grip.