Don't Gerrymander Your Heart - Lekh Lekha 5785

God's greatest gift to humans is the ability to talk to each other through difference.

Wednesday, Nov. 6, was not only the day after the election; it was also my brother’s birthday, so I gave him a call to chat. He lives with his family in Florida, where his wife grew up. In expressing his dejection over the way that the presidential election went, I was extraordinarily surprised to hear them both express that they were thinking of leaving Florida due to the way the political landscape has shifted there. And they are not alone - you may have seen a recent article in the New York Times about Americans moving for political reasons, to states and even neighborhoods where people agree with them. Polarization is happening not only in our hearts and minds.

And then of course I thought about Parashat Lekh Lekha, at the beginning of which our hero Avraham Avinu (our father Abraham) is told by God to leave his homeland and start anew. Why? Because he was living in a place where they worshiped idols, where, as perhaps the most famous midrash in the Jewish canon reports, his own father sold idols for a living. In order to start his new family, and the monotheistic tribe that would eventually become the Israelite nation, and then the Jews, could only be launched in a place free of idolatry.

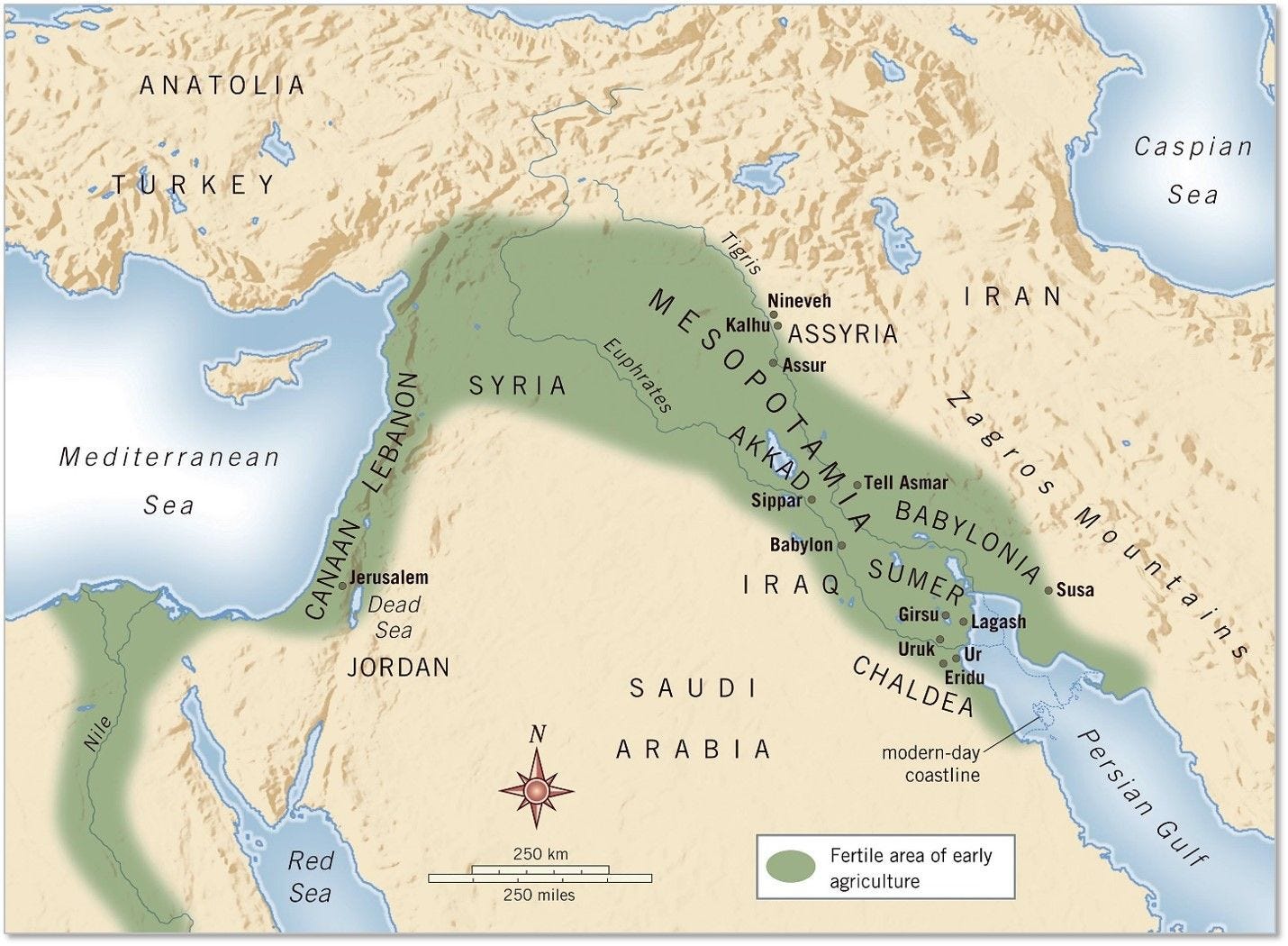

But wait a minute! The land of Canaan, to where Avraham and his wife Sarah relocated, was also an idolatrous place! The Canaanites surely had as many idols as the Chaldeans. And yet, that is where they built their new home, and of course that place would ultimately be renamed for Avraham’s grandson Ya’aqov, who eventually was given the name Yisrael - the one who struggles with God.

So why leave Ur, at the eastern end of the Fertile Crescent, in the first place? Why abandon your family and homeland to begin a life where idolatry also flourished? There must have been something else in play. Perhaps it was because, in order to launch this new nation, Avraham needed to be among others - NOT the people who raised him and whom he knew so well.

I was also reflecting on a commentary I heard about Migdal Bavel, the Tower of Babel, which appeared in Parashat Noah last week. We often think of that story as being about human arrogance, of trying to reach God by building a huge tower, for the purposes of “vena’aseh lanu shem,” so that the builders could “make a name” for themselves (Bereshit / Genesis 11:3). But one 18th-century Moroccan commentator, the Or HaḤayyim, Rabbi Ḥayyim ben Moshe ibn Attar, teaches us that the story is rather about diversity of thought. He wrote:

When the Torah reports that the people spoke one language and were of one mind about all important issues, the meaning is that they literally congregated together without spreading out at all. To prevent becoming scattered they built a single city. They built the tower as a landmark so that if any of them strayed too far from home he would be able to orient himself by seeing the tower from a distance. The "name" the Torah speaks of is the "name" of the tower, i.e. its visibility from afar, its significance. It was this very reluctance to comply with God's intention to populate various parts of the Earth which annoyed God… God therefore had to resort to some stratagem to frustrate their plan without interfering with their basic freedom of choice. God achieved this by confusing their uniform language. (Comment to Bereshit 11:1)

The Or HaḤayyim is telling us that Migdal Bavel was a symptom of the people’s reluctance to see anything beyond their immediate vicinity, their immediate family, the people around them, who all spoke the same language, lived the same culture, and agreed on everything.

This story is placed in the Torah just before we meet Avraham and launch him from Ur to Canaan. One conclusion that might be drawn from the proximity of these passages is that monotheism needed to be in a diverse environment, a place where multiple languages were spoken and a range of ideas could be found. It had to be created as an option in a place where Avraham was a stranger, a newcomer, thereby challenging the people of the land to think differently, to try out this new approach.

The alien concept of one God had to be sown in an environment where it was not the norm, and yet the people would also be potentially open to it. And that was not Ur. Avraham’s father Teraḥ, according to the midrash, could not wrap his brain around why Avraham had destroyed the idols in his shop and then cynically attributed the act to the biggest idol. That is all you need to know about Ur. The place where monotheism could take root was, rather, the place where people would struggle with God. It was Yisrael.

The greatest gift that God has given us is the ability to talk through difference, to work together even when we speak different languages.

The order to “lekh lekha,” to “get thyself out of town,” is hence more intellectual than it is geographical.

In all the anxiety and hand-wringing leading up to this election and in its wake, I am left with one particularly galling concern, and that is that we are failing to listen.

We are all so dedicated to singularity of thought, to purity of purpose, that we cannot see anything other than the towers we have built in separate camps, in separate cities. We heed only those voices which sound like our own, and we go to great lengths to ignore those which contradict our world view. We agree with those around us that we must “fight,” we must “win,” we must continue to raise our voices in protest, but not in dialogue. And so there is so much shouting, but little listening; so much fist-pumping, but little reasoned thought; so much playing to the id; but little desire to breach the divide between people.

Consider that our national elections are determined only by what amounts to a handful of voters in a few states. Everybody else is so set in their ways, unwilling to be swayed by the argument of somebody with whom we disagree. A couple of hundred thousand people, maybe 0.1% of the population of this nation, a tiny sliver, is effectively making the decisions for us.

I watch arguments go by online and I see that we are just talking past each other. There is no real engagement. So too on national television and radio, where the more shouting there is, the more anger and insult and seething and discomfort, the more we love it. We just cannot handle, or even imagine, respectful, thoughtful interaction with people with whom we disagree.

And let’s face it: people are really hurting, and they are seeking consolation, and they are seeking answers, and not always in the right places. We are all searching for a mashiaḥ, an anointed one, who will save us from all that ails us.

There is an expression in Israel, made famous by the singer-songwriter Meir Ariel, which captures the resilience of the Jews in the face of adversity throughout our history:

עברנו את פרעה, נעבור גם את זה

We survived Pharaoh, and we will also survive this.

Now is not the time for Lekh Lekha, of getting up and moving like Avraham Avinu, our father Avraham. Now is not the time for gerrymandering ourselves, either geographically or in our hearts, for huddling close to our respective towers of Babel.

It is rather the time to move in the spiritual sense. How do we make a better world, a better United States, a better Israel? By turning away from Migdal Bavel. By listening to each other, by talking through disagreement respectfully rather than demeaning one another. By seeking first to understand. By not reverting to the uniform jargon of one team or the other. By acknowledging that we cannot solve the problems we face until we hear each other’s voices and agree to work together to at least attempt to solve the very real challenges we face.

Every Shabbat morning at Congregation Beth Shalom we read, in the Prayer for our Country, that we must have the “understanding and courage to root out poverty from our land.” Of course we will disagree about what the best way to go about this is. But when I see the number of homeless tents along the bike trail downtown, when I consider the fact that a huge portion of Americans are just one unfortunate accident away from being destitute, when I see the ways in which we are killing each other physically and metaphorically, I remember that pointing fingers helps nobody. Assigning blame to this group or that, accusing one another of various -isms, or drawing lines of any kind only enables these problems to fester.

To have that understanding and courage to root out poverty, to improve our educational system for all, to ensure our bridges do not fall down, will require us to see the humanity of all around us, and to work across ideological and cultural differences for the common good.

If you are pleased with the outcome, do not gloat. If you are disappointed, do not despair. Instead, listen. Listen. And seek to understand. Forget the towers we have built, and seek out the company and opinions of the people who do not speak your language.

That is indeed how we will move forward together. That is how we will leave Ur and make it to the Promised Land.

I related strongly to this sermon. As a society and a community we really need to figure out how to live with and tolerate difference. If we don't do the work, we can't progress..

כל הכבוד