Centering Judaism, Part IV: Stuck in the Middle With You

Living Rambam's Golden Mean. This sermon is from Yom Kippur day, 5785.

You may recall that our theme for 5785 is “Centering Judaism.” On Rosh HaShanah I spoke about the joy at the center of living Jewishly and about Conservative Judaism being at the center of American Jewish life. On the evening of Yom Kippur, I spoke about Israel as the spiritual, cultural, and physical center of the Jewish world.

Today we are going to talk about living a centered life, as described by Maimonides.

There has been much consternation in the Jewish world over the last several years, particularly since the Charlottesville march in 2017, and perhaps peaking with the anti-Israel encampments which popped up on college campuses last spring, regarding the place of Jews in America, and our future in this land. I will freely admit that I have been struggling for months with a deep-seated discomfort that had never before struck me, that maybe America is not actually different. Maybe what has happened to Jews in virtually every place that they have lived and thrived and even joined the cultural elite throughout history: eventually the welcome mat is rolled up, and the Jews move on. Or worse.

And the challenge that I have had, week after week after painful week over the last year, is to remind all of you that hope remains before us, that we can continue to live and thrive and be proudly who we are, regardless of what is taking place in the world. And I will strive to continue doing just that.

And, along with the fact that you all know that my Zionism is firm and unwavering, I am also extraordinarily proud to be an American, and grateful that this nation has been not merely a haven, but also a fertile garden of growth and flourishing for the Jewish people.

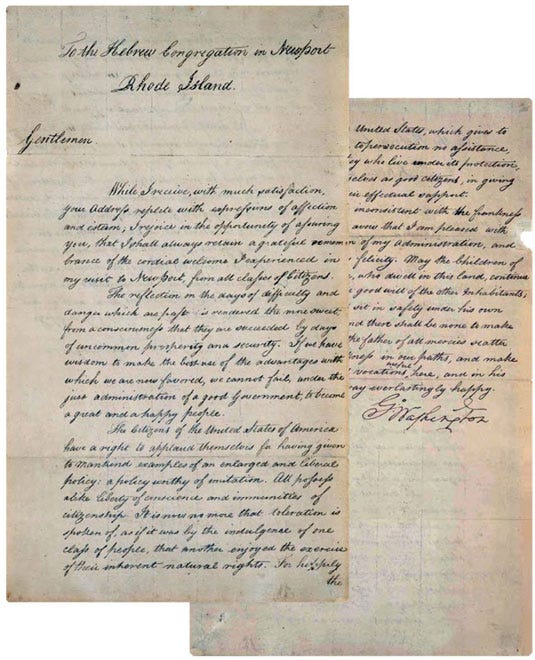

But of course, Di Goldene Medine, this land which some of our ancestors believed to have streets paved with gold, has not been without its challenges. We arrived on these shores first in 1654, although it took two years to get official permission from the Dutch government to stay legally. George Washington famously sent a letter to the Jews of Newport, Rhode Island in 1790, vowing that the government of the United States would give “to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance.” And waves of immigration from Germany and Eastern Europe later cemented the presence of Jews in the American tapestry. Nonetheless, there was always an undercurrent of antisemitism, sometimes submerged, but of course it never really went away. I know that many of us, including myself, are still reckoning with the fact that it is now resurgent.

And even knowing that, we have thrived here. And that is because America is a nation where the center dominates the extremes. There is clearly Jew-hatred on the fringes of American society. But the vast middle has always held it at bay.

Dr. Yehuda Kurtzer, President of the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem, recently gave a stunning address to a room full of American rabbis, titled “Our Golden Age.” He spoke about the fact that Jews have had a sort of covenant with America, one which enabled us to commit to the American project wholeheartedly.

“American Jews offer a prayer for America, oftentimes deeply rooted in sincerity. We have participated in its political culture as insiders rather than outsiders.

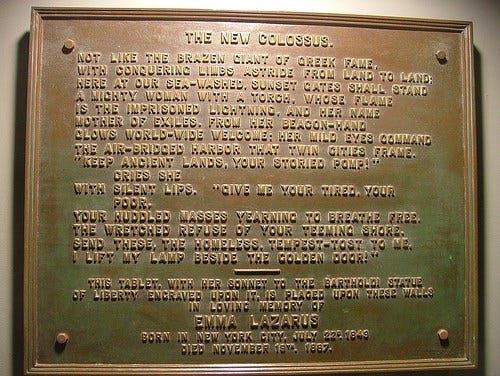

“Beyond what we did because it was our Jewish commitment, we American Jews also helped America think of itself in that way. It’s not a coincidence that one of our American Jewish tradition’s greatest poets, Emma Lazarus, is the author of the poem that shows up on the base of the Statue of Liberty, who envisions America as a place for the fulfillment of biblical ethics. When she says, ‘Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,’ it’s not hard to hear that as the American equivalent of the Bible’s 36 times that it mentions your responsibility to the widow, the orphan, and the stranger. We gave that to America. We saw it as part of what it meant to be Jewish in America, and we bequeathed it to America itself.”

Here at Beth Shalom, we of course offer that prayer for America as a part of our Shabbat morning service every week, and we continue to lean into that covenant. And Emma Lazarus’ poem is still there, still inscribed on the most potent symbol of America as a welcoming place to people from all over the world, including us.

And the hopeful note that I can provide is that we have to continue to look to that golden middle, the non-extreme, non-radical center where we are still welcome, where truly honest and inclusive democracy is still the reality.

As Jews, we incline toward that great American middle. And you might say that we have a religious imperative to do so.

I think that some of you know that my favorite night of the Jewish year, even more so than sharing the bimah with my daughter for Kol Nidrei, is the Tiqqun Leil Shavu’ot, which is held on the first night of Shavu’ot at the JCC. It is an opportunity to learn from rabbis and scholars from across the community. And my favorite part of the evening is what happens after the official program ends at 1 AM. At that point, a group of hearty souls from our congregation continue to learn Torah into the wee hours, starting with a discussion at my house, where I have typically taught something from Rambam, Maimonides, one of the most powerful voices on the Jewish bookshelf, who speaks to us from 12th-century Egypt.

Rambam wrote a tractate as part of his halakhic magnum opus, Mishneh Torah, called Hilkhot De’ot, the laws of human dispositions. And one of the essential ideas of Hilkhot De’ot, which we have learned on my back porch at 2 AM on Shavu’ot is the idea of the Golden Mean: that in all characteristics of our personalities, we should strive to be in the middle, rather than at the extremes. Rambam writes (De’ot 1:4), [SUMMARIZE - don’t read the below]

הַדֶּרֶךְ הַיְשָׁרָה הִיא מִדָּה בֵּינוֹנִית שֶׁבְּכָל דֵּעָה וְדֵעָה מִכָּל הַדֵּעוֹת שֶׁיֵּשׁ לוֹ לָאָדָם

The straight path: This [involves discovering] the midpoint temperament of each and every trait that man possesses [within his personality.] This refers to the trait which is equidistant from either of the extremes, without being close to either of them…

For example: he should not be wrathful, easily angered; nor be like the dead, without feeling, rather he should [adopt] an intermediate course; i.e., he should display anger only when the matter is serious enough to warrant it, in order to prevent the matter from recurring.

Similarly, he should not desire anything other than that which the body needs and cannot exist without, as [Proverbs 13:25] states: "The righteous man eats to satisfy his soul."

Also, he shall not labor in his business except to gain what he needs for immediate use, as [Psalms 37:16] states: "A little is good for the righteous man."

He should not be overly stingy nor spread his money about, but he should give charity according to his capacity and lend to the needy as is fitting.

He should not be overly elated and laugh [excessively], nor be sad and depressed in spirit. Rather, he should be quietly happy at all times, with a friendly countenance.

The same applies with regard to his other traits.

And, Rambam concludes by assuring us, “This path is the path of the wise.”

The goal is to find the Golden Mean of all of our personality traits. You should not be too happy nor too sad. You should not be too hotheaded nor too passive. And if you find yourself approaching the extremes of any characteristic, you should correct your behavior to be in the middle.

Rambam’s framework of course accounts for individual differences in personality, and encourages continuous introspection and re-assessment. It does not mean, of course, that you can never be angry or laugh so hard you bust a gut. But the goal is ultimately to be temperamentally stable, to average out to a healthy middle path.

On this day of Yom Kippur, a day on which we are obligated to consider our behavior and course corrections for the coming year, we should absolutely be thinking about Rambam’s strategy. Have I yelled too much at my kids? If so, maybe I need to dial it back. Have I been insufficiently responsive to my spouse? If so, perhaps I need to work on our relationship. Have I given enough tzedakah? Am I honestly purchasing and consuming what I truly need? Is the pursuit of my wants obscuring what constitutes true happiness and crowding out what is meaningful and joyful? These are all worthy questions for this day.

And writ large, I think we can also expand Rambam’s vision not only to personal traits, but also those of the society in which we live. We live in a society that seems so angry: two attempts on the life of a former president; campus protests which emphasize not free speech and the exchange of ideas but hateful graffiti and threatening chants; the ever-present binary notion that you are either with me or against me. Rambam, if he were magically transported eight centuries forward to today, would surely survey the landscape and sadly shake his head.

We should continue to look to the middle, to support the center, and to avoid the extremes to which we are being pushed by algorithms, media and public figures. As I have said in the past, we are not Orthodox, and we should avoid orthodoxies of all kinds. To that end, here are a few suggestions:

I know this is going to be really difficult in the next few weeks, but it might not be such a terrible thing if we were all to try to be a little less obsessed with the news. If you have managed to beat back the temptation to be constantly connected to what is going on elsewhere at all times, mazal tov! For all the rest of us who are obsessing, not merely following, but obsessing about one thing or another, let me remind you that excessive reading/watching/posting about the news actually probably will not help anything or give you any more control. But it might make you more anxious. So find that golden mean and consider cutting back if necessary.

As cartoonist David Sipress recently put it in a New Yorker cartoon, “My desire to be well-informed is currently at odds with my desire to remain sane.”

Something which observers of American society have noticed in recent years is that, as religion has retreated from a position of primacy, political engagement has filled the void it has left, and probably not for the better. Our politics, like religion, have become tribal. Just as our religious commitments engendered a certain amount of loyalty and contention, the same is now true of our politics. And while religious intermarriage has become the norm, we are busy dividing ourselves into immiscible political groups with a widening chasm between them.

This cannot be good for the future of America.

Now, I cannot very well stand before a roomful of Jews and suggest that we care less about politics. But I can remind us all, as I did on the first day of Rosh HaShanah, that the tools of Judaism will help keep us sane as our politics turn ever crazier. Reciting words of prayer in synagogue, relaxing with family on Shabbat and during holiday meals, learning the wisdom of the Jewish bookshelf - these things will not only pull you away from the nonsense of the news cycle, but also might give you a longer, more reasoned perspective. Let’s keep Judaism as our religion and prevent politics from consuming us all.

Another related thought: social media. The Surgeon General of the United States, Dr. Vivek Murthy, issued a warning back in May 2023 that it can be harmful to children and adolescents. But guess what? It may not be that good for adults either. Social media has altered the way we think and the way we interact with others. The Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari has just published a new book on this subject, in which he discusses how the algorithms of social media are destroying us. I have spoken about this before and I do not need to go into the details, but if you find yourself always on Facebook or Instagram, you might want to consider finding a way of limiting your usage (like, for example, taking a break from it on Shabbat!), and spending more time with real people in person.

I have found that even people who are deeply divided over politics are much less likely to despise people with whom they find themselves in actual conversation, in each others’ presence and in real time. So put down your phone, close your laptop, and get out there and talk to people!

One way of doing so, by the way, is by joining Beth Shalom’s ḥavurah program. A ḥavurah is a small group within the congregation - no more than 20 people - who meet regularly to participate in shared activities: having dinner together, or a discussion, or going to a show, or for a pleasant walk in Frick Park, or any other social activity. We launched this program about a year and a half ago, and we are hoping to build it by inviting more folks in. This is a big congregation, and one way to build a greater sense of connection within the congregation is to meet in smaller subsets. The more of us who participate in a ḥavurah, the more interconnected and the stronger Beth Shalom will be. You’ll be receiving more info about the next opportunity to join some time this fall.

***

I know that many members of this congregation were at the Jewish Federation of Greater Pittsburgh’s commemoration of the Oct. 7 Hamas attack this past Monday evening. As you may know, at Beth Shalom we have the custom of marking yahrzeits not on the secular date, but according to the Jewish calendar, and that date is the 22nd day of Tishrei, which is the festival day of Shemini Atzeret. We will do so on that day, and then we will make the transition to Simḥat Torah in the evening, the most joyous day of the Jewish year.

It is worth noting that on Sukkot, and some years on Shemini Atzeret, we read the book of Qohelet, Ecclesiastes, the book that attempts to answer the question of how we find meaning when we are weary of the world. And the most famous passage in Qohelet is the opening of Chapter 3, the “Catalogue of Times.” You know this best from the Pete Seeger song made famous by the Byrds, “Turn, Turn, Turn.” But the original goes like this:

לַכֹּ֖ל זְמָ֑ן וְעֵ֥ת לְכׇל־חֵ֖פֶץ תַּ֥חַת הַשָּׁמָֽיִם׃ עֵ֥ת לָלֶ֖דֶת וְעֵ֣ת לָמ֑וּת עֵ֣ת לָטַ֔עַת וְעֵ֖ת לַעֲק֥וֹר נָטֽוּעַ׃… עֵ֤ת לִבְכּוֹת֙ וְעֵ֣ת לִשְׂח֔וֹק עֵ֥ת סְפ֖וֹד וְעֵ֥ת רְקֽוֹד׃

A season is set for everything, a time for every experience under heaven: …

A time for being born and a time for dying,

A time for planting and a time for uprooting the planted;...

A time for weeping and a time for laughing,

A time for wailing and a time for dancing;...

Most of the time of our lives is spent in the middle: the time between being born and dying; the time between planting and harvesting, when our crops are growing, and again between harvesting and planting once again, when the land lies fallow. Rambam’s Golden Mean may be found in the everyday struggle to keep ourselves whole and healthy and consistently moderated.

Perhaps Qohelet, in pointing to all of the seemingly oppositional times, is reminding us that the ONLY way we can handle all of the complex happenings that life throws at us is by hewing to the center, by keeping the extremes at bay, by seeking a middle path.

And while we of course must wail in mourning at the appropriate time, we must always remember that we will someday dance again.

Reality surely falls in the middle, and that is where we need to be - to be centered, to be balanced, to be sensitive to all the possibilities of life.

***

Yizkor Coda

As we transition to the service of Hazkarat Neshamot, recalling the souls, I am going to share with you part of a brief story from Israel from last December. You may recall that there were three Israeli hostages held in Gaza who were tragically killed by IDF troops during an operation. One of the three was Yotam Haim, and his mother Iris wrote an account for the collection, One Day in October. Here is a brief piece from her essay:

***

One day during the shiv’ah, a woman approached me and said, “Iris, I’m the wife of the commander of that battalion, and all his soldiers are completely devastated; none of them are functioning; they just want to die.” I said to her, “No, I have to speak to them right now!” She said to me, “But they’re in Gaza,” so I decided to record a voice message for them. I took the phone and sent them a message, spontaneously - I didn’t sit and plan it, or write it out, I just recorded whatever came out of my mouth, and this is what I said to them:

“Hi, this is Iris Haim, Yotam’s mother, and I wanted to tell you that we love you, we love you very much, and we’re not angry, and we’re not judging, and what you did - with all the pain and regret - was probably the right thing to do at that moment. I beg you not to think twice when you see a terrorist; you have to kill him and not be afraid that you’ll kill a hostage. And as soon as you can, please come here to us; we want to see you so much, to look you in the eye, and to give you a big hug.”

And the soldiers came; they came as soon as they got out of Gaza. They came, these sweet soldiers with bowed heads, and they sat here with us, and we hugged them, and we told them that we were not angry. We were not there, we do not know what happened there, and we had heard about all kinds of tricks and ploys that Hamas tried in Gaza - how they would pretend to be hostages and speak in Hebrew, then attack. We were not angry at them. We just hugged them, and we cried together, and we told them about our wonderful Yotam.

The circumstances of Yotam’s death were especially challenging, but his family was able, in their grief, to muster some compassion for the young men who made a horrible mistake.

Yotam was 28, and the rest of the essay speaks of who he was and the great joy he brought to his family and friends.

No matter when those whom we love leave this world, and no matter how, we always must remember their lives as a gift to us, whether a few precious years or many, many decades. And living a centered life reminds us that we must cherish what we receive, the precious memories we have, even when we grieve.