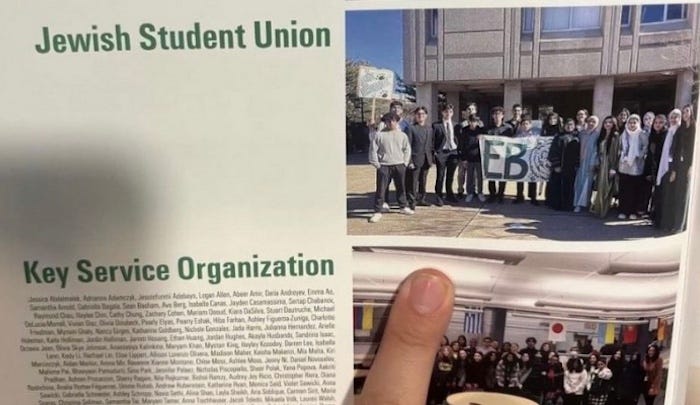

An unsettling incident unfolded this week in New Jersey, where a high school yearbook erased the Jewish Student Union from its pages. On the page where the JSU’s photo and names of club members were supposed to be, there were no names, and an unrelated photo of Muslim students appeared where the JSU photo was supposed to be. This literal erasure was quickly seized upon by the mayor of East Brunswick, New Jersey, Brad Cohen, and the local Jewish Federation, among others. There were a smattering of similar yearbook incidents throughout the country.

Now, think for a moment how you might react to this news. Do you find it troubling? If so, why?

Maybe one reason that this might be upsetting is because of your sense of being part of a collective, the Jewish people. That is, you know that as a Jew you share many things with other Jews: a sense of belonging, aspects of culture, a common history, an ancient language which is now spoken (in its modern reincarnation) by half of our people, a shared literary and ritual tradition.

Maybe this story upsets you because, even though it is a relatively minor slight, it cuts quite deeply into our sense of connection to the Jewish people.

Now, the Torah is somewhat confused on the difference between a people and a nation. The terms “Benei Yisrael” and “am Yisrael” are used interchangeably, but they are not the same. “Benei Yisrael” is plural: it suggests, like the plural English word people, a whole group of individuals, and it specifically suggests that we are all children of Ya’aqov - that is, a family. But when we say “Am,” a singular word, we are suggesting not just the people themselves, but everything else that comes along with nationhood. The Torah frequently refers to “Amkha,” Your nation, connoting our relationship with God.

I would like to propose that the reason so many seemingly minor incidents, which have increased in frequency and intensity over the last eight months, are so painful is because of our sense of being a part of Am Yisrael, the nation of Israel, rather than simply Benei Yisrael, the people of Israel. October 7th and its aftermath is forcing us to define ourselves in the context of nationhood. Let me explain.

Parashat Bemidbar is entirely about the people of Israel. It opens with identifying the tribes and their leaders, then continues with a census of men eligible to serve as soldiers, lays out the structure of the Israelite encampment, and then describes the roles of the Levi’im (Levites). It’s almost as if it is written by a bureaucrat: numbers and administrative duties.

One might say that the sense of Am Yisrael, of the nation of Israel, is here muted by the simple, clerical character of the text.

Thank God for the Qedushat Levi, Rabbi Levi Yitzhaq of Berdichev, who, in noting the total of 603,550 that the Torah counts in the census, tells us that this number corresponds to the number of letters in the Torah. Every single letter counts; so too, as people, each of us belongs, each of us is important as an essential piece of the collective Jewish nation. The loss of a single Jewish person is a great loss to our nation. We are all interconnected.

Now, let’s face it: We have always lost Jews. Throughout Jewish history. Consider the expulsions and wars throughout our history, which were never bloodless. Consider the forced and intentional conversions, the pogroms, forced conscriptions, the Holocaust, and of course the forces of assimilation.

It is, in fact, absolutely amazing that we are still here. It is a tribute to our resilience.

And given that history, it is not entirely surprising that the modern period awakened a contemporary Jewish sense of nationhood, which in turn yielded the Zionist imperative: to seek self-determination in our historical homeland, the one from which we were exiled for a second time 2,000 years ago, the one which we always face in prayer, the one which we invoke in our liturgy multiple times every day. וַהֲבִיאֵֽנוּ לְשָׁלוֹם מֵאַרְבַּע כַּנְפוֹת הָאָֽרֶץ וְתוֹלִיכֵֽנוּ קוֹמְ֒מִיּוּת לְאַרְצֵֽנוּ. “Bring us safely from the four corners of the Earth, and lead us in dignity to our land.”

The Jewish story is different from that of any other nation. The French were never exiled from their land. The Chinese did not need to approach the UN for statehood.

Thanks to the Babylonians and the Romans, we were scattered among all the nations of the world. And we held onto the dream of return for two millennia in our rituals, our prayers, our Torah conversation. The Babylonians effectively created religious Zionism in the 6th c. BCE; the anonymous author of Psalm 137 wrote (v. 1):

עַ֥ל נַהֲר֨וֹת ׀ בָּבֶ֗ל שָׁ֣ם יָ֭שַׁבְנוּ גַּם־בָּכִ֑ינוּ בְּ֝זָכְרֵ֗נוּ אֶת־צִיּֽוֹן׃

By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat and wept as we thought of Zion.

And in the current moment, the dramatic rise of anti-Jewish activity around the world elevates the need for Zionism. We are not disparate, unconnected groups davening in Pittsburgh or Buenos Aires or Kiev or Singapore. We are a nation with a homeland.

Three weeks ago, the Federation’s celebration of Yom HaAtzma’ut (Israel’s Independence Day) began with a pride-filled march from Beth Shalom to the JCC. About 300 folks marched, including many members of this synagogue. We were arrayed in blue and white and holding Israeli flags aloft.

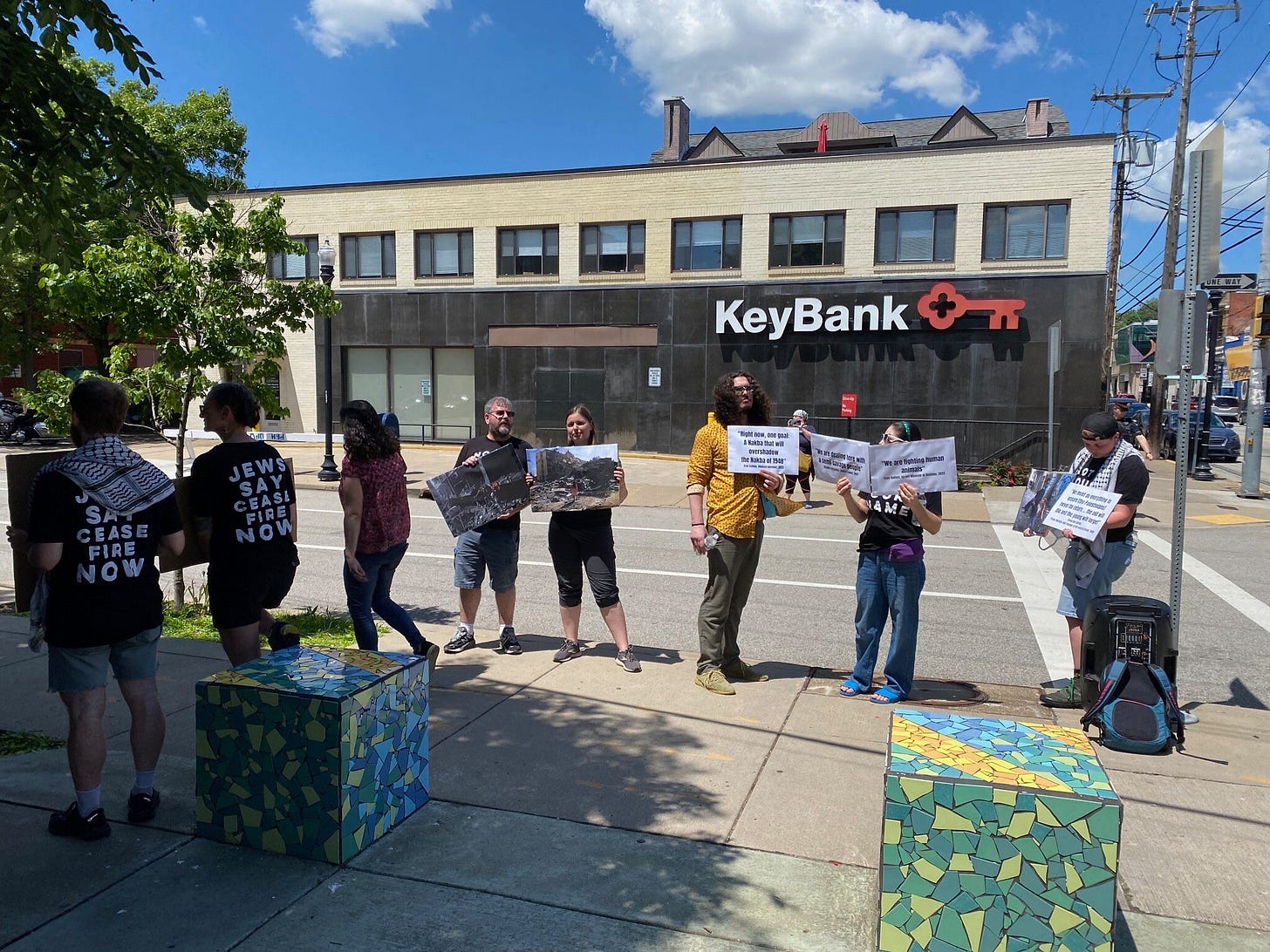

As we came to the intersection of Murray and Darlington, we encountered a group of eight members of Jewish Voice for Peace, silently holding aloft posters displaying dead children in Gaza. JVP is an anti-Zionist organization.

Their position (which you can find on their website) is that Zionism is a 19th-century, colonial movement that places European Jews at the top of a nationalist hierarchy and by definition dispossesses and displaces Palestinians. In describing the State of Israel, they freely use terms like apartheid, genocide, racist, etc. They also feel quite strongly that anti-Zionism need not overlap with anti-Semitism.

Now, while it may be true that political Zionism emerged in the latter half of the 19th century in Europe, it is absolutely not a European movement. On the contrary: Zionism was brought into being by people who saw no future for the Jews among other nations, whether in Europe or anywhere else. The manifesto of the BILU in 1882, called for establishing a Jewish national home in Israel, following major pogroms in Russian cities. It opens with Hillel’s words from Pirqei Avot (1:14): אם אין אני לי מי לי? If I am not for myself, who will be for me? Then it says the following:

Sleepest thou, O our nation? What hast thou been doing till 1882? Sleeping and dreaming the false dream of assimilation. Now, thank God, … the pogroms have awakened thee from thy charmed sleep. Thine eyes are open to recognize the cloudy structure of delusive hopes. Canst thou listen silently to the flaunts and the mockery of thine enemies?

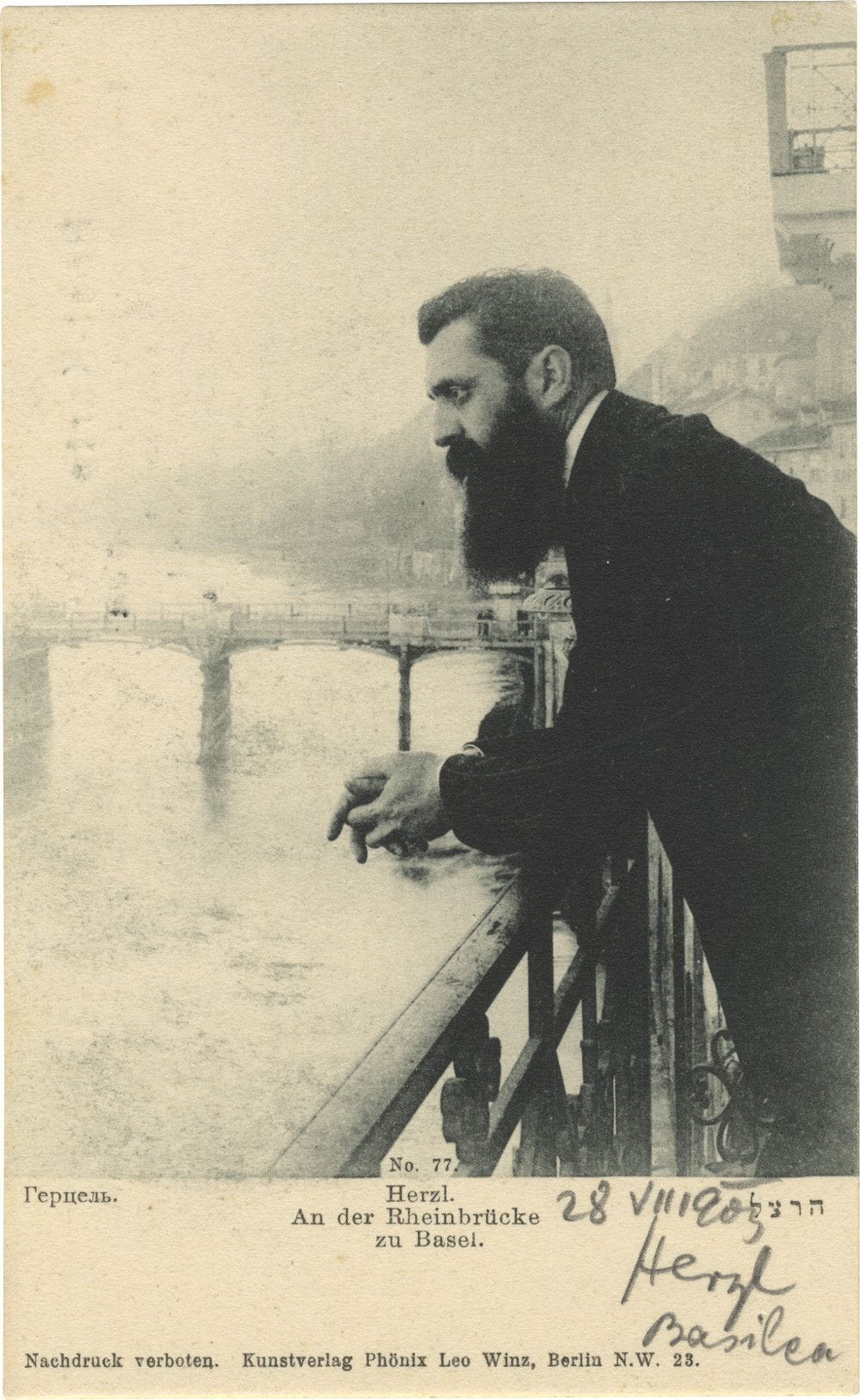

What motivated Theodor Herzl to convene the First Zionist Congress in 1897? It was his experience as a journalist covering the antisemitism of the Dreyfus affair in the mid-1890s. Herzl saw that even though Jews had gained citizenship in European nations, he was convinced that they would never be truly French or German or Hungarian, and that the Jews needed their own state. And of course, he was not alone.

And Zionism was already baked into the Jewish psyche. We had never abandoned that dream; modern political tools made Jewish self-determination through the establishment of a nation in Israel a possibility. The flowering of Jewish redemption had arrived.

The Zionist mission was never “colonization” or “displacement” or “dispossession” or “genocide” or any such post-modern epithet. The goal was fulfilling the ancient dream of return, an essential plank of Jewish nationhood.

Anti-Zionism denies that we are a people with a shared destiny, a shared culture and ritual and yes, a homeland. And given all of what has happened in the last eight months, we know now more than ever since World War II, that we need that homeland.

Zionism is, in fact, integral to what it means to be a Jew. Anybody who denies this is, as they say today, gaslighting. You don’t have to live in Israel to be Jewish, but we cannot allow the world to forbid us the right to do so. We need Israel like the French need France and the Chinese need China.

(Another claim of anti-Zionist groups like JVP is that the very existence of the State of Israel creates antisemitism. This is a baseless and offensive charge; it is blaming the victim. There was certainly no shortage of anti-Jewish activity prior to 1948, or even 1882.)

If there is anything to be learned from the current moment, it is that the BILU and Herzl were right. When the new encampment at the Cathedral of Learning was established this week, one of the protestors’ demands was for Pitt to sever its relationship with Hillel. After the encampment was vacated, they retracted this particular demand, but added that it was “endorsed by concerned members of our Jewish community who wish to see it replaced with genuine Jewish community spaces unconnected to a violent state.”

Anti-Zionism is a denial of who we are as a nation. And that is fundamentally antisemitic. The Jews who claim to be anti-Zionist are myopically denying their historical roots; while they may claim membership in the Jewish people, they dismiss those elements of our shared heritage which make us a nation. They have opted out.

One final thought: You don’t have to be anti-Zionist to criticize the Israeli government. Israelis do it all the time, and you know that I have no great love for the current coalition; a new round of elections cannot come soon enough. But I am a zealous supporter of the Jewish nation in the wider sense, and committed to the essential truth that the multi-cultural, multi-religious, democratic State of Israel is an essential part of who we are today.

Am Yisrael Ḥai. The nation of Israel lives and thrives.

Thank you for the sad reminder that the urge to polarize the nations and communities in which we live has always been baked into our humanity. As a feature within the broad intertwined, categories of good and evil, it has always risen to disrupt the better angels in all of us. But perhaps that is part of a larger plan; a reinforcement of the underlying message of Judaism, which is that the outcome of each of our actions is the result of choice. For better or for worse, it confirms our human identity.